Why "Hardware is Hard" Misses the Opportunity

Saying “hardware is hard” blinds founders to the bigger opportunity: designing behaviors in an era where AI and robotics are reshaping demand. Focusing on unmet needs, defensibility and real market traction turns “features” into enduring businesses worth funding.

Pancrazio Auteri

Nov 15, 2025

Picture this: robotic tiles beneath your feet that reconfigure themselves in real-time, creating infinite walking paths in virtual reality. They simulate stairs, lifting and lowering as you climb virtual mountains or descend into digital caverns. This is CirculaFloor from University of Tsukuba's VR Lab, invented by Professor Hiroo Iwata and his team over a decade ago. Yet most VCs would pass on this and many other hardware innovations without a second thought.

Hardware is Hard. We Pass

The phrase "hardware is hard" has become venture capital's polite rejection for an entire category of innovation. But here's what that reflexive response misses: hardware isn't the product, it's the platform. Those robotic tiles aren't just about precise motor control and sensor fusion. They're an enabler for immersive training simulations, therapeutic rehabilitation experiences, architectural walkthroughs and entertainment applications we haven't imagined yet. The real question isn't whether the hardware works, it's what ecosystem of value it unlocks.

In my work advising hardware startups, I see a consistent pattern. Capital arrives not when founders perfect their technology specs or hit performance milestones, but when they reframe the conversation entirely. The shift happens when teams move from "our actuators have 0.1mm precision" to "physical therapists spend $200k annually on equipment that only addresses 30% of mobility recovery scenarios." When the pitch evolves from features to the size of the problem, the intensity of demand drivers and critically, how many others want to build applications on top of the innovation, that's when term sheets appear.

Consider MEMS. The invention of these tiny sensors didn't create one successful company, it unleashed an entire industry. InvenSense rode this wave to a $1.3 billion acquisition by TDK in 2016. Their motion tracking sensors became the invisible foundation that let thousands of software and system integrators create previously impossible experiences: accelerometers enabling motion gaming in every smartphone, pressure sensors transforming automotive safety, gyroscopes making consumer drones possible.

Today's "hard" hardware innovations, from novel actuators to advanced materials to specialized robotics, hold similar platform potential. Look at Figure, developing humanoid robots, recently valued at $39 billion. Or Anduril Industries, building autonomous defense systems, now worth billions thanks to its Lattice OS enabling platform. Recent waves came from Arduino, the open-source hardware platform that sparked the maker movement and enabled millions of developers to prototype products; it was acquired by Qualcomm just one month ago to accelerate its edge computing and AI strategy. And even more recently, a week ago Majestic Labs ai completed a $100M Series A round to increase 1,000x (yes!) the memory capacity of AI systems. What's the struggle here? The essential memory infrastructure is not keeping the pace with computing power: with training clusters doubling every five months, this innovation allows to rebalance memory and compute with a huge impact on the economics of datacenters and new AI models.

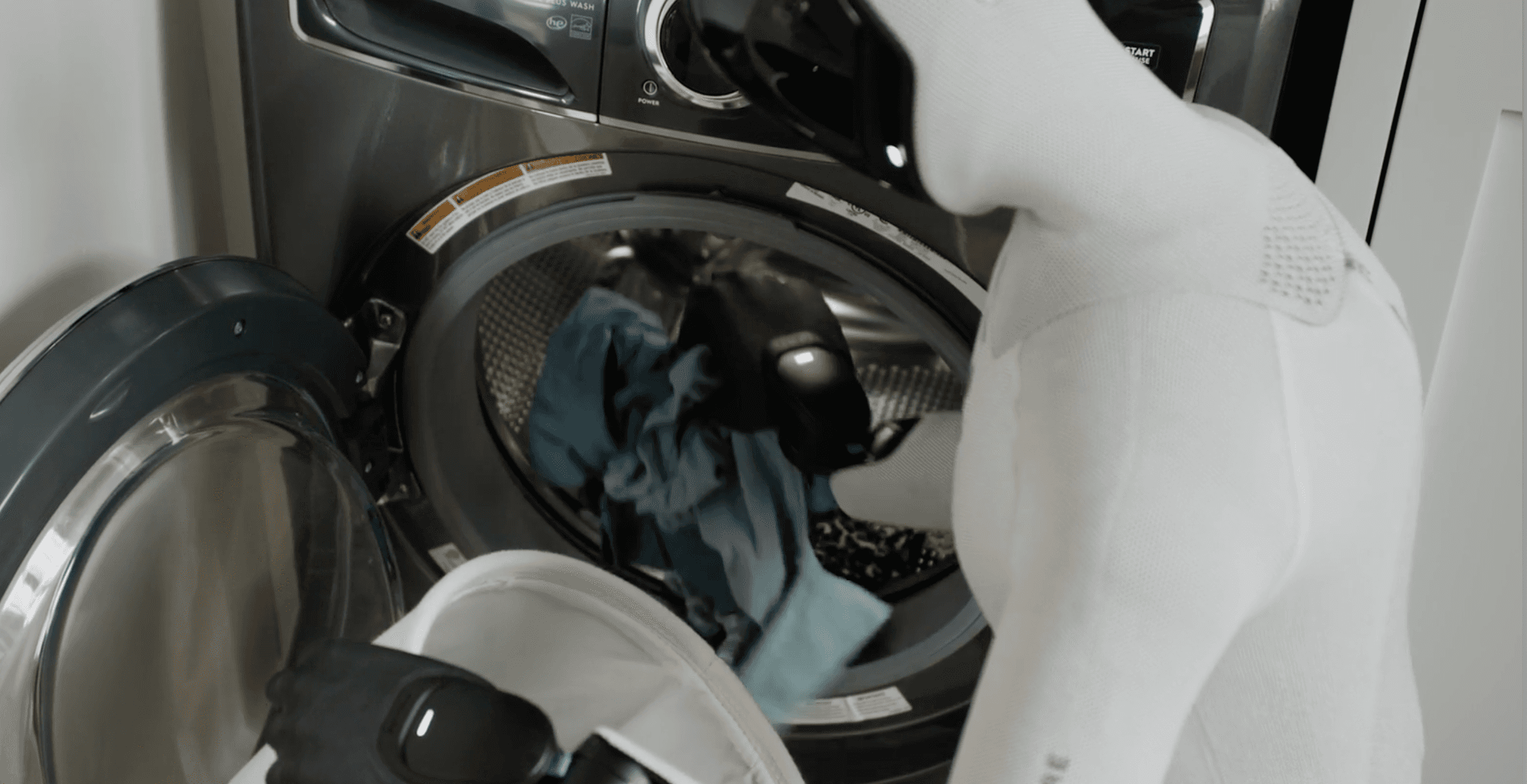

The latest Figure 03 model can move into the home as well as in a warehouse or a factory

Technology Transfer from Academia?

Yet there's a brutal challenge that most investors underestimate: transferring technology from academic labs to commercial reality. University research optimizes for novelty and publication. Industry demands reliability, manufacturability, cost structures and time-to-market. This gap isn't just technical, it's cultural, operational and financial. The researchers who can articulate a breakthrough often lack the network and commercial instincts to scale it. When hardware innovation lands inside a large corporation, it gets absorbed into existing distribution channels, manufacturing infrastructure and customer relationships. Risk is distributed across a portfolio. When it lands in a startup, most elements of the business model must be built from scratch while racing against a finite runway.

HW Startup Challenges

The startup must simultaneously prove technical feasibility, achieve product-market fit, establish supply chains and convince customers to bet on an unproven vendor. These aren't just different challenges, they're different games entirely. VCs who compare startup hardware opportunities to corporate R&D projects are using the wrong mental model. Founders focusing solely on specs and innovation without a serious go-to-market plan are wasting their time. Success requires looking past the hardware specs to understand: What current struggles does this eliminate? What value does it unlock? How big is the desire of others to build on top of it? That's where billion-dollar outcomes hide.

Successful capital raising starts with presenting the right team for the challenge (why us?), a market shift with a big, expanding TAM (why now?) and a moat long enough to take off. Founders investing time in selecting the right VCs and presenting a visionary future with a capital-efficient plan have the best odds.

Question for you, investors and founders

So here's my question for this network: what are your hardware innovation success stories? If you're an investor, what made you say yes when the conventional wisdom said no? If you're a founder, what did you learn about navigating the gap between invention and commercialization?

The next generation of transformative companies won't be pure software plays, they'll be hardware innovations that become platforms for entire ecosystems. Let's share what actually works in funding and scaling them.

Ad maiora,

Pan Out